I was recently asked to give a talk about Hadley’s package testthat. Any discussion of testthat cannot be in isolation - we have to put it into the wider software development context. I think this is the first time that I have used the words software development on this blog, and for many R users, thinking of their code as software development, may not be familiar. In particular, I think that those of us who have come to Data Science or statistical computing from a statistical, especially academic background, tend to have a poor understanding of some common practices among developers that would actually make their lives much easier1. Version control is one I’ve talked about before (recognise this?), but another is unit testing.

Having a second person look over your code: QA or 2i, whatever you want to call it, is an incredibly important part of the analytical process in many organisations. Sadly, in my experience this is often done badly, especially if there is not a strong community of R users (assuming we are talking about R - although we needn’t be) and a strong idea of ‘what good looks like’.

What if we could:

- write our code in a way that makes QA much easier, and

- actually automates much of this testing in a more thorough and consistent way, as a matter of course.

As is often the case, software developers have been grappling with this problem for a long time, under much more trying conditions, and Test Driven Development (TDD) is one approach to doing this.

In this post, I am going to give a very simple example of TDD in an analytical context, using testthat2

A simple example

Imagine that we want to normalise a vector, which is a common task for machine learning.

Let’s think for a second what we would need to do. Mathematically it might look something like this:

\[\vec{y} = \frac{\vec{x}-\min{x}}{\max{x}-\min{x}}\]Where:

- $\vec{y}$ is our normalised vector,

- $\vec{x}$ is our target vector.

Before setting out to write the code, there are a few things we already expect to be true of $\vec{y}$. We can list some of these expectations, for example:

- Elements of $\vec{y}$ should all be between $0$ and $1$

- $\vec{y}$ should be the same length as $\vec{x}$

- $\vec{x}$ should be scalar (

numericin R)

Let’s try this. First let’s create a vector x to play with based on a uniform distribution with a minimum of $10$ and a maximum of $100$

# First set a seed, so you see what I see. 1337 is the best seed, obvs.

set.seed(1337)

x <- runif(100, min = 10, max = 100)

x## [1] 61.86894 60.82679 16.65912 50.84791 43.59513 39.81857 95.28670

## [8] 35.30056 32.08636 23.14393 98.14873 99.43458 84.46229 27.45841

## [15] 98.31929 12.27057 97.51496 93.14170 40.52257 32.19215 86.42474

## [22] 75.16794 14.19562 23.83103 60.63348 98.32831 93.85968 90.87534

## [29] 52.28139 99.55073 90.84471 19.14559 76.55116 30.62085 80.95286

## [36] 67.75592 97.18704 77.16716 36.34789 29.35718 75.89200 84.76711

## [43] 59.39237 69.28600 29.30290 18.26361 37.77561 48.54409 14.59077

## [50] 43.61292 96.65508 74.03164 65.57352 46.55795 79.67136 35.21346

## [57] 22.71488 63.00307 57.30615 69.83769 90.69782 32.85174 87.78906

## [64] 93.87432 21.75408 21.83684 99.97440 57.46373 31.22632 59.55834

## [71] 43.47002 81.76885 36.83209 15.78632 72.99225 43.14955 22.61422

## [78] 32.80217 53.02225 63.74990 98.74448 79.33006 13.42352 26.63911

## [85] 57.33332 90.73812 76.93809 52.15916 31.41670 95.16210 86.16433

## [92] 65.04514 76.25626 56.25007 70.54470 47.79791 71.16260 33.31253

## [99] 31.82564 97.39483Now to normalise:

y <- (x - min(x))/(max(x) - min(x))

y## [1] 0.56552110 0.55363852 0.05003829 0.43985917 0.35716298 0.31410257

## [7] 0.94655077 0.26258814 0.22593987 0.12397810 0.97918360 0.99384495

## [13] 0.82313066 0.17317186 0.98112835 0.00000000 0.97195743 0.92209342

## [19] 0.32212959 0.22714600 0.84550657 0.71715643 0.02194941 0.13181252

## [25] 0.55143433 0.98123124 0.93027985 0.89625243 0.45620380 0.99516926

## [31] 0.89590309 0.07838908 0.73292797 0.20923004 0.78311610 0.63264445

## [37] 0.96821844 0.73995157 0.27452984 0.19482167 0.72541216 0.82660628

## [43] 0.53728319 0.65009053 0.19420273 0.06833271 0.29080876 0.41359104

## [49] 0.02645497 0.35736575 0.96215304 0.70420038 0.60776074 0.39094499

## [55] 0.76850451 0.26159511 0.11908611 0.57845241 0.51349610 0.65638084

## [61] 0.89422825 0.23466665 0.86106258 0.93044682 0.10813108 0.10907470

## [67] 1.00000000 0.51529280 0.21613368 0.53917564 0.35573644 0.79242006

## [73] 0.28005069 0.04008659 0.69234916 0.35208241 0.11793841 0.23410150

## [79] 0.46465106 0.58696782 0.98597642 0.76461296 0.01314590 0.16383024

## [85] 0.51380597 0.89468774 0.73733974 0.45481013 0.21830440 0.94513002

## [91] 0.84253737 0.60173620 0.72956548 0.50145473 0.66444222 0.40508302

## [97] 0.67148750 0.23992063 0.22296709 0.97058771Now we can test our assumptions:

What is the range of $\vec{y}$

range(y)## [1] 0 1How long is $\vec{y}$?

length(y)## [1] 100What class is $\vec{y}$?

class(y)## [1] "numeric"All good so far, but this is quite long winded, and if we had to check that our code worked every time like this, we would have to write a lot of code. Second we would need to manually check our little tests manually, and we might conceivably notice a failed test. If we started to litter our code with a lot of these ad-hoc tests, might also start to break another of the tenets of good software development: DRY or Don’t Repeat Yourself.

The TDD process

Now lets do the same again from a TDD perspective. Of course, in order to do this, we need to functionalise our code, which may also be something relatively new to a statistical scripter The benefits become obvious pretty quick - generalising our code into functions allows us to generalise our code, whilst also hiding away the complexities, and keeping our code nice and tidy.

The TDD process looks something like this:

- Write a series of tests

- Run tests and see if the tests pass

- Write the code

- Run tests again

- Repeat

Write a series of tests & Run them

Just as in the previous section I discussed some of our expectations of what our code will produce, in TDD we formalise these expectations by explicitly writing tests first, before we even start to think about the code in our function. We know that our tests will fail first time round, as there is no code to make them pass, but spelling out our expectations of what our function will produce, is an important step in its own right.

This is where testthat comes in. Testthat is a unit testing frame work for R (we think of our function as a unit of code), that makes TDD very easy.

So, to re-use my normalisation example: first I define my tests:

A simple test from testthat looks like this:

library(testthat)

expect_equal(

range(normalise(x)),

c(0, 1)

)This test encapsulates our expectation that after normalisation, our vector will have a minimum of $0$ and maximum of $1$.

Usually we want to package up a series of tests together to test a particular function. Here’s how we can do that:

library(testthat)

test_that(

"Test the normalise function",

{

# Tests run in their own environment, so we need to recreate a vector to

# test on:

x <- runif(100, min = 10, max = 100)

# Check that the min = 0 and the max = 1

expect_equal(

range(normalise(x)),

c(0, 1)

)

# Check that y has the same length as x

expect_equal(

length(normalise(x)),

length(x)

)

# Check that the resulting vector is numeric

expect_is(

normalise(x),

'numeric'

)

# Here I go one step further, and check the output against a specific and

# easily checkable vector. I just did the sums in my head!

test_vector = c(1, 2, 3)

expect_equal(

normalise(test_vector),

c(0, 0.5, 1)

)

}

)## Error: Test failed: 'Test the normalise function'

## * could not find function "normalise"

## 1: expect_equal(range(normalise(x)), c(0, 1)) at <text>:15

## 2: compare(object, expected, ...)So we run this code, and the tests fail.

Why?

Because could not find function "normalise".

Of course - we have not written it yet!

Write the code

So lets write our function now. We define our function to take one input which should be a vector.

normalise <- function(x) {

# Run the normalisation as before

y <- (x - min(x))/(max(x) - min(x))

# Return the y object (if we didn't do this, nothing would happen!)

return(y)

}Run tests again

So with that written, lets try again with our tests.

test_that(

"Test the normalise function",

{

# Tests run in their own environment, so we need to recreate a vector to test on:

x <- runif(100, min = 10, max = 100)

# Check that the min = 0 and the max = 1

expect_equal(

range(normalise(x)),

c(0, 1)

)

# Check that y has the same length as x

expect_equal(

length(normalise(x)),

length(x)

)

# Check that the resulting vector is numeric

expect_is(

normalise(x),

'numeric'

)

# Here I go one step further, and check the output against a specific and

# easily checkable vector. I just did the sums in my head!

test_vector = c(1, 2, 3)

expect_equal(

normalise(test_vector),

c(0, 0.5, 1)

)

}

)This time we don’t get anything returned. These tests are silent. If they pass, they pass silently; if they fail they let us know. So all good.

Repeat

At this point, we might start to think about the other ways that we might test our function. What would happen for instance if someone passed something to it that it was not expecting, for example:

- A single scalar instead of a vector.

How might we want our function to work in these case? Let’s say we want to handle this cases very simplistically by just returning an error. We expand our test suite to include this:

test_that(

"Test the normalise function",

{

# Tests run in their own environment, so we need to recreate a vector to test on:

x <- runif(100, min = 10, max = 100)

# Check that the min = 0 and the max = 1

expect_equal(

range(normalise(x)),

c(0, 1)

)

# Check that y has the same length as x

expect_equal(

length(normalise(x)),

length(x)

)

# Check that the resulting vector is numeric

expect_is(

normalise(x),

'numeric'

)

# Here I go one step further, and check the output against a specific and

# easily checkable vector. I just did the sums in my head!

test_vector = c(1, 2, 3)

expect_equal(

normalise(test_vector),

c(0, 0.5, 1)

)

# Add cases where we want to raise a warning

expect_error(

normalise(1)

)

}

)## Error: Test failed: 'Test the normalise function'

## * normalise(1) did not throw an error.These tests fail.

Why?

The error message says normalise(1) did not throw an error; so we know what we have to do…

normalise <- function(x) {

# Raise error in input x has length < 1

stopifnot(length(x) > 1)

# Run the normalisation as before

y <- (x - min(x))/(max(x) - min(x))

# Return the y object (if we didn't do this, nothing would happen!)

return(y)

}Now that we have updated the function, lets run the tests again…

test_that(

"Test the normalise function",

{

# Tests run in their own environment, so we need to recreate a vector to test on:

x <- runif(100, min = 10, max = 100)

# Check that the min = 0 and the max = 1

expect_equal(

range(normalise(x)),

c(0, 1)

)

# Check that y has the same length as x

expect_equal(

length(normalise(x)),

length(x)

)

# Check that the resulting vector is numeric

expect_is(

normalise(x),

'numeric'

)

# Here I go one step further, and check the output against a specific and

# easily checkable vector. I just did the sums in my head!

test_vector = c(1, 2, 3)

expect_equal(

normalise(test_vector),

c(0, 0.5, 1)

)

# Add cases where we want to raise a warning

expect_error(

normalise(1)

)

}

)So all the tests pass silently!

Tidying this all up

So this is all a bit long-winded.

You don’t really want to be repeating these long strings of tests over and over again; it would be nice if we could just get these to run automatically, and this is possible using the function testthat::test_dir() which will look into a directory, and run all the tests in that directory beginning with the prefix test_.

Better yet, we write a package, and when we build our package containing our collection of functions, our tests will be run automatically. In fact, a good example of how to organise your tests can be seen in the automated tests that ship with the testthat package itself; there are a lot of them!

We can take this even further, and use some code coverage tools (like https://codecov.io) to look at our code and tell us which functions have been tested, and which haven’t. For example, in my govstyle package we can see that around 80% (at time of writing) of the code is covered by tests:

Drilling deeper, I can see that of the two functions that make up the package, one of them is only 60% covered:

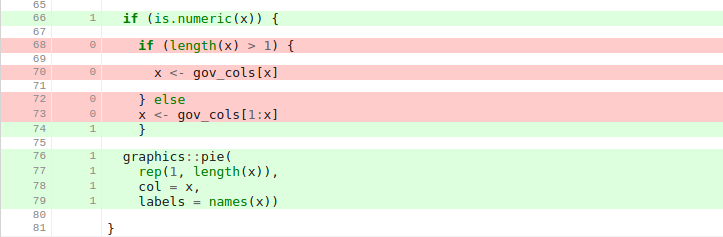

I can even see the offending lines of code, which are in this case an untested if statement:

I don’t think I need to worry about this too much.

I’ve written about package development before - and there are a lot of other benefits to writing packages, not least the fact that for teams, it can allow us to enshrine business knowledge into a corpus of code that is inseparable from the documentation of that code. It’s well worth the relatively modest learning curve.

sessionInfo()## R version 3.3.1 (2016-06-21)

## Platform: x86_64-apple-darwin14.5.0 (64-bit)

## Running under: OS X 10.11.6 (El Capitan)

##

## locale:

## [1] en_GB.UTF-8/en_GB.UTF-8/en_GB.UTF-8/C/en_GB.UTF-8/en_GB.UTF-8

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] testthat_1.0.2

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] R6_2.1.3 magrittr_1.5 formatR_1.4

## [4] tools_3.3.1 crayon_1.3.2 rmd2md_0.1.2

## [7] stringi_1.1.1 knitr_1.14 stringr_1.1.0

## [10] checkpoint_0.3.16 evaluate_0.9-

Props to Software Carpentry for righting this wrong. ↩